As I was exploring tree-like shape generation for my procedural art project fresco, built on top of p5.js, I came across the interesting problem of generating fruits at the extremity of some branches, and making sure they never intersect with other branches as well. In its simplest form, this problems boils down to detecting when a segment (the branches) intersect a circle (the fruit) and avoid its occurrences. In this article we’ll explore a simple, yet elegant way of solving this problem.

DISCLAIMER: This article is a re-post of an older Medium blog post I made a while back.

Let’s do math!

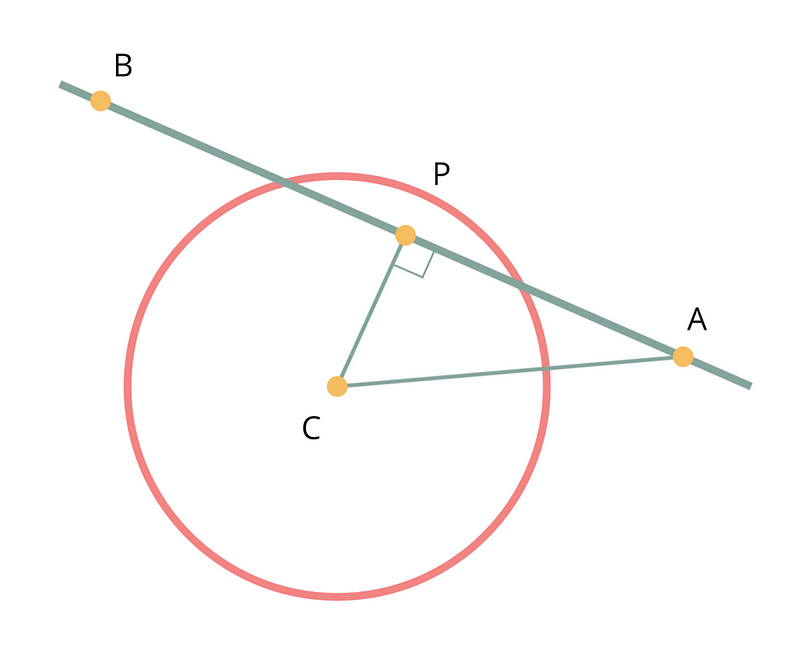

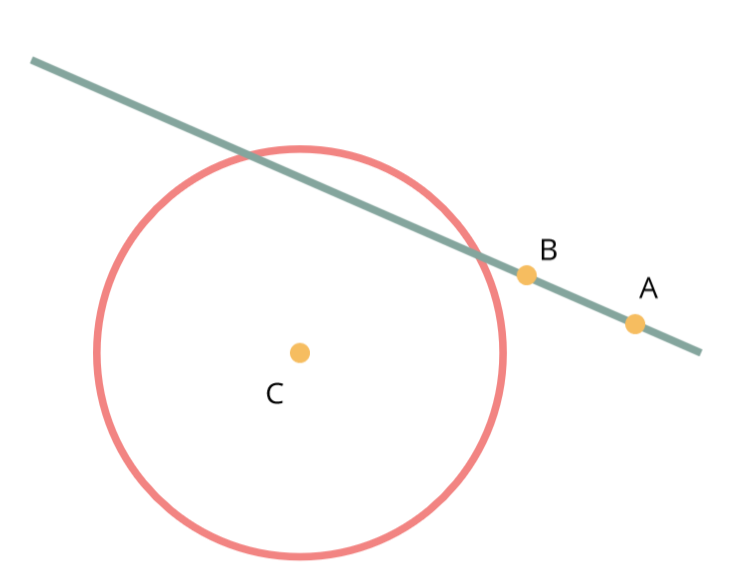

What we want to know is whether the segment $[AB]$ (a branch section) intersects the circle of center $C$ and radius $R$ (the fruit). $A$ and $B$ are the extremities of the segment in this case.

I tried a few approaches, including actually solving for the intersection points between the support line of the segment and the circle, but these often require some calculus, which in my experience is error prone, and may lead to rounding uncertainties. Instead I took a vector based approach which requires very little calculus. Even better, the little calculus left to do is handled by the p5.js library for me. Hurray!

Step 1: Does the support line intersect the circle?

Let’s first consider the line going through $A$ and $B$ without worrying about the segment being finite.

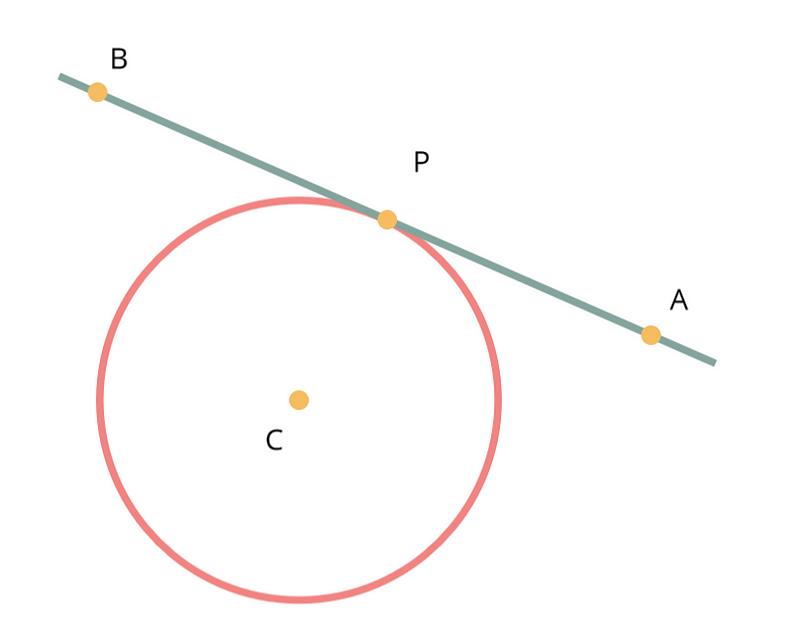

The closest point to $C$ on the line is called the orthogonal projection (noted $P$) of $C$ on the line $(AB)$. There is “orthogonal” in its name, because the line from $P$ to $C$ is actually orthogonal (perpendicular if you prefer) to the line. Now, because $P$ is the closest point to $C$, if this point more than one radius apart from $C$, which is another way to say that $P$ is outside the circle, we know that any other point on the line will also be outside the circle. So all we have to do, is to find this projection point $P$ and measure its distance to $C$. If we have a look at the drawing, we can see that (and that’s basically what Chasles’ rule gives you)

\[\vec{AC} = \vec{AP} + \vec{PC}\]In addition, we know that the dot product of 2 orthogonal vectors is 0. Hence we can easily find the distance from $A$ to $P$.

\[\vec{AC} . \vec{AB} = \vec{AP} . \vec{AB} + 0 = |AP| \times |AB|\] \[|AP| = \frac{\vec{AC} . \vec{AB}}{|AB|}\]This means we can deduce the position of $P$:

\[\vec{P} = \vec{A} + |AP| \times \frac{\vec{AB}}{|AB|}\]All we are left to do is to compute the distance to point $C$. This is where we can also introduce a small standard optimization. If you remember the Pythagorean theorem, you’ll know that the length of a given vector (“the hypothenus”) is the square root of the sum of the square of the vector x and y components (“the other sides of the triangle”). However, computing square roots is quite expensive in computers (I guess in real life it is not easy either 😥). The good news is, given distances are always positive, if $d1 > d2$, then $d1^2 > d2^2$. So we can actually compare the square of the distance of $P$ to the circle center $C$ and the circle radius, which is to say, check if

\[||\vec{PC}||^2 \leq R^2\]To do this we can use the dot product again:

\[||\vec{PC}||^2 = \vec{PC}.\vec{PC} \leq R^2\]Awesome! we now know whether the support line intersects the circle. If the support line does not, then your segment won’t either!

Step 2: From line to segment.

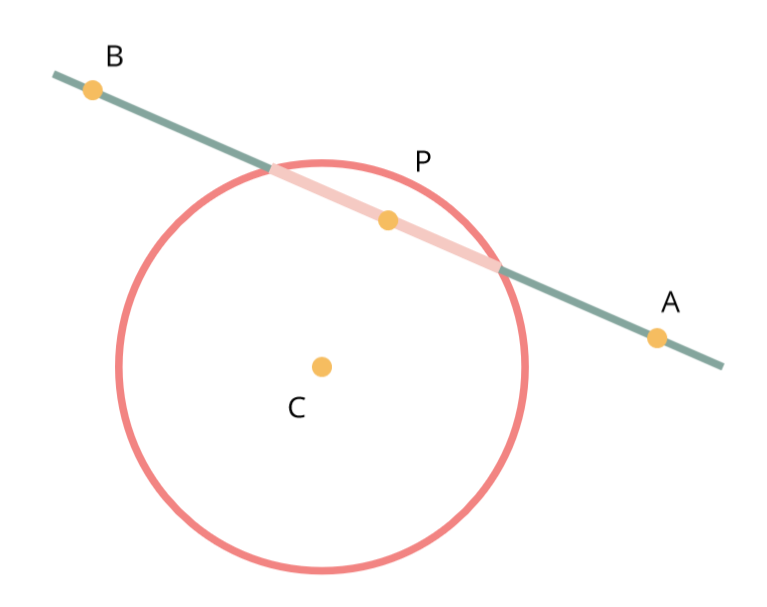

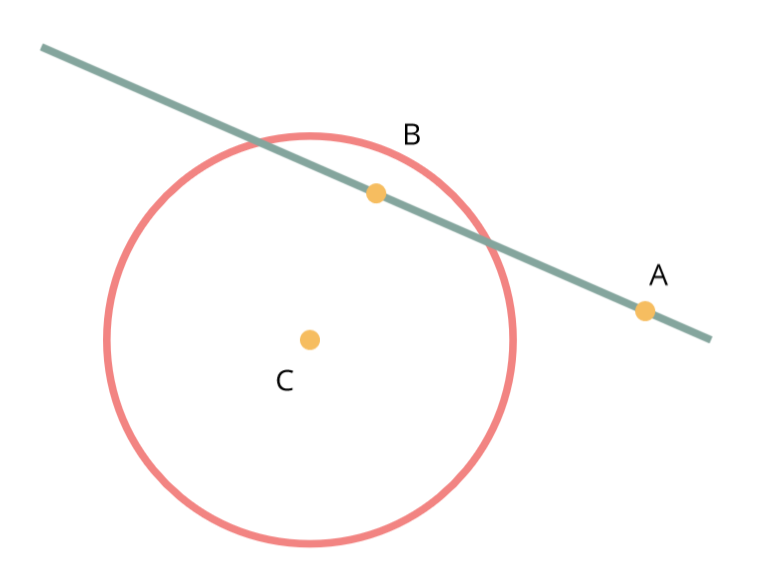

From here on, we now assume the line (AB) does indeed intersect the circle. You have 3 different possible cases based on where the segment extremities are.

Case 1: The extremities are on each side of the intersected area.

In this case, the previously computed projection point should lie between $A$ and $B$. As such, it should be closer to $A$ than $B$ is. Again, for speed we can check the square of the distances and thus we simply check whether

\[\vec{AP}.\vec{AP} \leq \vec{AB}.\vec{AB}\]Case 2: One (or both) end(s) is (are) inside the circle

In this case we can simply check whether one of the ends is close enough to the center. We can reuse the formula we used for finding the distance of the projection P to the center C:

\[\vec{AC}.\vec{AC} \leq R^2\]or

\[\vec{BC}.\vec{BC} \leq R^2\]Case 3: Both ends are outside the circle.

If the segment does not fall in either of the previous cases, it means that both extremities of the segment lie on the same side of the circle and thus that the segment does not intersect the circle.

Bonus case:

There is an “edge” case where the projection point is right on the circle, meaning the line is actually tangential to the circle.

In this case it is up to you to choose whether you count this as an intersection, on a use-case basis. If you do want to check for this case (meaning you think this does not count as an intersection), you need to check whether the point P is exactly at a distance of one radius from the center $C$. Because of all the fun of storing non integer numbers (floating point numbers) in a computer, I would actually check instead whether the difference between the radius and the distance $PC$ is smaller than a small number $\epsilon$, typically $1e-7$:

\[\vec{PC}.\vec{PC} - R^2 \leq \epsilon\]Coding time

We can now convert this to code. I’ll write this in Javascript, using the amazing p5.js library, on which my project Fresco is based:

/**

* Computes the square of the distance between 2 points

* @param {p5.Vector} A First point.

* @param {p5.Vector} B Second point.

* @returns {Number} Squared distance between the points.

*/

function distSquared(A, B) {

let AB = B.copy().sub(A);

return AB.magSq();

}

/**

* Checks whether a segment intersects a circle

* @param {p5.Vector} A First end of the segment.

* @param {p5.Vector} B Second end of the segment.

* @param {p5.Vector} C Circle center.

* @param {Number} R Circle radius.

* @returns {Boolean} true if intersection there is.

*/

function doSegmentIntersectCircle(A, B, C, R) {

// compute the direction of the line

let dir = B.copy().sub(A).normalize();

// compute the vector from A to C

let AC = C.copy().sub(A);

// Compute the distance from A to P

let AP = AC.dot(dir);

// Compute the posistion of P

let P = dir.mult(AP).add(A);

let R2 = R * R;

// check if the projection is inside the circle

if (distSquared(P, C) > R2) return false;

// check if the projection point is closer to A than B is

if (distSquared(A, P) <= distSquared(A, B)) return true;

// check if either end point is inside the circle.

if (distSquared(A, C) <= R2 || distSquared(B, C) <= R2) return true;

return false;

}

Conclusion

I hope this somewhat graphical solution helped you on your journey to master programmatic art 😄. One strength of it is it also generalizes very well to higher dimensions. So if you ever want to know whether a segment in 3D space intersects a sphere, well, you don’t have to change one thing! Wouhou!

Either way, this is only the first of a series of articles on the results of my explorations of (one very tiny specific niche method for generating) tree-like structures. So stay tuned for more geometry and procedural generation goodies!